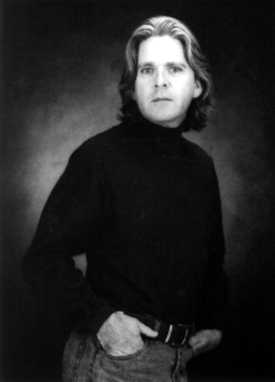

michael askill

Mitte

der 70er Jahre startete Michael Askill seine Karriere

als Erster Schlagzeuger des Sydney Symphony Orchestras

und Begründer der Perkussionsgruppe Synergy.

In seinen Kompositionen verschmelzen die Rhythmen

der verschiedenen Kulturen mit Avantgarde-Elementen.

Vieles ist für Tanzaufführungen geschrieben

und in Zusammenarbeit mit anderen Musikern entstanden

(Tekbilek, Hudson, Riley Lee u.a.)

Mitte

der 70er Jahre startete Michael Askill seine Karriere

als Erster Schlagzeuger des Sydney Symphony Orchestras

und Begründer der Perkussionsgruppe Synergy.

In seinen Kompositionen verschmelzen die Rhythmen

der verschiedenen Kulturen mit Avantgarde-Elementen.

Vieles ist für Tanzaufführungen geschrieben

und in Zusammenarbeit mit anderen Musikern entstanden

(Tekbilek, Hudson, Riley Lee u.a.)

Michael Askill, the composer, is also a percussionist.

In most of the world's great musical traditions, that

fact might not be worth noting. But Western music

has, in a sense, spent several centuries reinventing

the wheel: the Western classical tradition has often

treated percussion instruments as an afterthought.

From the Renaissance to the Romantic era, percussionists

were second-class musicians. Only in the 20th century

have composers begun to treat this ancient family

of instruments with the respect it gets in Arabic,

African, or Asian music. Askill, formerly Principal

Percussionist with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra,

has spent the past twenty–five years quietly

but effectively carving a niche for music that is

percussion based, whether written by his contemporaries

or by Askill himself.

Askill's music draws as heavily on world music traditions

as it does on Western jazz, rock, and classical music.

And being a percussionist, he says, definitely colors

the types of music he creates. "I feel most comfortable

composing in the traditional sense, on manuscript

with percussion instruments." As this compilation

shows, though, there is little traditional in Askill's

compositions. "That's why I work with the people I

do," he explains. "They bring me the improvising traditions

that they are a part of Riley Lee's Japanese flute,

or Omar Faruk Tekbilek's

Turkish instruments and improvise within my context.

Whether that's 'composition' or not, I'm not sure."

To the listeners who have enjoyed Askill's work with

the group Synergy Percussion, or his evocative scores

for the Sydney Dance Company, such distinctions won't

matter much. It is enough to marvel at Askill's eclectic

blend of Asian and Western musics (a natural one for

an Australian composer), and of electric and acoustic

instruments (natural for a composer of the late 20th

century).

Askill was born in Durban, South Africa, to a British

father and a South African mother of British descent.

Foreseeing some of the problems Apartheid would bring,

the family moved first to Birmingham, England, and

then, in 1957 when Askill was five, to Australia.

("The Australian Government were offering passages

from the UK to Australia for 10 pounds!" Askill remarks.)

He grew up in Adelaide, which may be one of the smaller

of Australia's major cities but which nevertheless

has a vibrant arts scene.

Like many of his contemporaries, Askill studied

in Europe, spending some of the early '70s in Strasbourg,

France at the invitation of Les Percussions de Strasbourg.

Returning to Australia in 1974, he began playing in

the fledgling new music scene in Sydney, meeting like-minded

percussionists and eventually forming the group which

became Synergy Percussion. Askill held the post of

Principal Percussionist with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra

for many years during the 1970s and '80s. But even

while working squarely in the Western Classical tradition,

with perhaps the premier orchestra in Australia and

the Pacific, Askill was stretching out, working with

Nigel Westlake's Magic Puddin' Band (a progressive

rock group) and Synergy Percussion, among others.

In 1982, he traveled to New York to study with Elden

'Buster' Bailey and Morris Lang, both then with the

New York Philharmonic, and wound up studying jazz

as well with David Samuels and David Friedman (both

of whom, coincidentally, would record In Lands

I Never Saw (13015-2)

for Celestial Harmonies in 1987).

Rhythm In The Abstract: Selected Pieces 1987-1997

(15030-2) has

Michael Askill's name on the cover, but his music

is essentially a collaborative art, and has been throughout

his career. While studying in Strasbourg in the early

'70s, Askill first met the Australian dancer and choreographer

Graeme Murphy, with whom he would later form a ground–breaking

interdisciplinary tandem. "He was in a French company

called Ballets Felix Blaska," Askill recalls, "and

we saw one another when they came to Strasbourg. They

were working then with two of the best French percussionists,

doing dance with live music." The idea of dance with

live music is not new, but in 1991 Graeme Murphy and

Michael Askill began developing an extraordinary way

of blending music with dance and musicians with dancers

that remains one of the most remarkable collaborations

in the world of dance theater.

"In 1991 Graeme came to see Matsuri (13081-2),

Synergy's show with Riley Lee, Satsuki Odamura and

a butoh dancer, Chin Kham Yoke", Askill says,

"and asked Synergy to work with him." The result was

Synergy With Synergy, a program as successful as it

was big. "Free_Radicals came about because Graeme

wanted to continue the dance/percussion idea on a

more portable scale," Askill explains. "The Synergy

show was just too big to be economical to tour." In

all of their collaborations, the musicians were not

only visible, but actively involved in the movements

on stage. In Free_Radicals (15027-2),

the percussion arsenal included the dancers' bodies.

In the same piece, Askill turned a rhythmic pattern

into a sequence of numbers, which in itself is not

unusual...but he then gave it to several members of

the dance troupe to recite, each in a different language.

In Salome (15031-2),

the integration of musicians and dancers was even

closer, with members of the dance troupe acting as

a chorus and adding to the percussion texture. In

their latest collaboration, Air And Other Invisible

Forces, the musicians float around the stage on platforms

that move between the dancers. Together, Graeme Murphy

and Michael Askill have created a composite art that

blurs the traditional distinction between dancers

and musicians...and ironically, their collision of

art forms, so exceptional in the West, strongly echoes

the close ties between music and dance found in Africa,

Indonesia, and other world traditions.

Like many Australian musicians of his generation,

Askill finds his position as a Western–trained

musician in a Pacific Rim country to be a great source

of inspiration. With Synergy Percussion, another one

of his most important and long–standing collaborations,

world music—and especially Asian music—has

played a major role. "Synergy was interested in commissioning

new works from young and established Australian composers,

but also interested in working outside of the new

music scene, which was active but small," he recalls.

"As percussionists, we were passionate about the roots

of drumming and tried to find an approach to the interpretation

of contemporary percussion music that would reflect

our location within the Asia–Pacific region."

The search for a meeting point was a splendid success.

As the group amassed a collection of instruments from

Japan and the Asian continent, Synergy Percussion

began to approach even the works of American composer

John Cage and other contemporary figures with a distinctly

Pacific approach.

Working with Synergy helped to crystallize Askill's

own approach to world music. "In Australia we have

a bird called the bower bird," he says. "It goes around

picking up blue objects to put in its nest. I gather

lots of bits together and arrange them in my own personal

style." As this compilation shows, there is no such

thing as a 'typical' Askill score. While percussion

remains at the heart of his music, Askill is also

fond of flutes, voices, electronic sounds and digital

samples. In his best works, Salome (15031-2),

for example, there is also a strong narrative sense,

and he has often done more structured scores for film,

dance, and even a children's circus. But he has also

embarked on some very unusual, "free–range" projects,

where the only given is the line–up of musicians

and instruments. These projects have produced some

unlikely but appealing results. As a percussionist,

Askill seems to find it easy to move between styles.

After all, percussion is common to all of them. Even

though Askill has long since relinquished his post

with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, classical works

with a heavy percussion part, like Carl Orff's Carmina

Burana, will occasionally lure him back to the

concert stage. Askill was familiar with the teachings

of Orff's longtime associate percussionist Karl Peinkofer

in Munich—a fact regretfully unknown to the record

company at the time of the Celestial Harmonies recording

of the Orff-Schulwerk series (13104-2,

13105-2 and 13106-2).

This set of recordings covers more than a decade

and includes musicians as diverse as composer/synthesist

Nigel Westlake, Japanese koto player Satsuki

Odamura, and the Australian Aboriginal musician David

Hudson. Listeners who know of Askill's many recordings

for Celestial Harmonies and Black Sun may recognize

some of these pieces, but this compilation also includes

some revised versions of previously released works,

and offers a first glimpse at Askill's new score for

Graeme Murphy's Sydney Dance Company, a work that

uses digital samples from Celestial Harmonies' impressive

roster of traditional world music recordings.

In fact, there is now a substantial body of music,

most (but not all) of it from Australia, in the Celestial

Harmonies catalogue because of Michael Askill. Enlisted

to produce Daniel Binelli's Tango (15020-2),

essentially because he knew where to find the Argentine

musician, Askill rapidly became the conduit by which

some of Australia's finest early music, world music,

and contemporary ensembles were heard for the first

time outside their own country. "He has been much

more than a musician recording for the label," says

Celestial Harmonies president Eckart Rahn. "He brought

in much inspiration, great musicians and engineers,

and opened up the Australian scene for us. That led

to us having recorded and released internationally

probably more Australian music than any other record

company."

Michael Askill's own work and his tireless championing

of a large variety of other people's music from Down

Under has led to Celestial Harmonies' release of the

complete Hildegard von Bingen edition (13127-2

and 13128-2) by

Stevie Wishart's vocal ensemble

Sinfonye, as well as the brilliant recording of Der

Schwanengesang (The Swan-Song [13139-2])

by German baroque composer Heinrich Schütz, produced

by Askill in the great concert hall of the Sydney

Opera House and performed by Roland Peelman's Song

Company ("a massive project," Askill says in his usual

understated way). Among the numerous Australian artists

whom Askill brought to Celestial Harmonies and thereby

into the international limelight was Michael Atherton

who recorded first with Askill on Shoalhaven Rise

(15019-2)

in 1995. Atherton in turn went on to record several

disks in his own name. And once the floodgates were

opened, a stream of Aussie talent, ranging from Prof.

Margaret Kartomi (who produces Celestial Harmonies'

Music of Indonesia series 14155-2,

13175-2 and 13182-2)

to James Ashley Franklin (who reunited with Satsuki

Odamura on Water Spirits [13160-2]),

enriched the Celestial Harmonies catalogue.

It is rare to find a musician who dedicates so much

of his time and energy to his fellow musicians, and

does so with such enthusiasm. Askill has in turn been

an artist recording his colleagues' music, a producer

sharing his experience and expertise in the recording

studio, and, in an informal but very effective way,

an ambassador-at-large for his country's culture.

Askill says his favorite compositions are the ones

that have a narrative quality. Rhythm In The Abstract:

Selected Pieces 1987-1997 (15030-2)

uses his music to tell the story of Askill's varied

career. It can be recounted simply enough in words:

the early studies in Europe, the first private recordings

in Strasbourg in 1973; stints in the Australian contemporary

music scene and with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra.

The formation of Synergy Percussion in 1974; work

with Nigel Westlake's Magic Puddin' Band and the world

music group Southern Crossings in the 1980s. And finally,

beginning in 1994, the first international releases

on the Celestial Harmonies and Black Sun labels, and

of course his meetings with Omar Faruk Tekbilek, David

Hudson and Riley Lee. But the story is told more appropriately,

and the narrative made more satisfying, by letting

the music speak for itself.

John Schaefer

New Sounds, WNYC-FM, New York City

(based on conversations with Michael Askill)